The effect of an after-school “learning space” on student academic achievement and their confidence in MYP Science

Abstract

Twenty seven 10th grade MYP Science students across two classes attending Northbridge International School of Cambodia participated in an action research study exploring the question, “What is the effect of an after-school “learning space” on student academic achievement and their confidence in MYP Science? A two group pre/post design measured change in confidence and academic achievement in MYP Science. The comparison group completed an MYP Science unit on Car Safety before the learning space was opened whilst the experimental group completed the unit with the learning space support available. Results identified no statistically significant changes between the two classes with confidence or academic achievement. However, a statistically significant change was identified with the confidence of the sub-sample of English as a second language (ESL) learners indicating a positive impact of the intervention. Yet the lack of regular attendance by students may have impacted the results and resolving this issue will be the key focus of a further action plan.

Introduction

With a gross national income of only $880 (The World Bank, 2014), to be able to send your children to a fee paying international school in Cambodia is a strong indicator of economic success within families. However, due to the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, many of the parents who are now enrolling their children in an international education did not have a typical educational experience, let alone one with an international bias. For during their youth, schools were converted into torture and detention centers and often the educated were intentionally targeted for being enemies of the state. Hence, they did not receive any consistent schooling. Therefore, those Cambodians who have now succeeded, and indeed are affluent enough to send their children to an international school, did not find success based on education but are more likely to credit their success to an incredible combination of luck, hard work and a willingness to seize an opportunity in difficult times. These experiences appear to have impacted the student motivation and willingness to put in the time required for academic success. Furthermore, many of my students are faced with the additional challenge of being English as a second language learners (ESL) without the support of competent English speaking parents/ guardians. Difficulties with the lingua franca of our school often cause students to get accustomed to failure which can furthermore impact their motivation to succeed academically.

During a discussion with my own grade 9 homeroom about suitable learning environments, the idea of an after-school space, which also contained teacher assistance when required, was suggested. This idea was further developed into the creation of the learning space, found in a multipurpose room after school from Monday to Thursday and supported, with the presence of a teacher.

Literature studies had identified the positive benefits of similar homework projects (Cosden, Morrison, Gutierrez, & Brown, 2004), especially for ESL students. However, a study of homework centers (Bender & Stahler, 1996) had also identified regular attendance as having a major impact on the success of students in such programs. The type of tasks being given to students as homework was also identified as an issue (Sanacore, 2002).

This study has is designed to produce quantitative evidence in response to the question, “What is the effect of an after school study “learning space”on student’ (particularly ESL students) academic achievement and their confidence in MYP Science assessment tasks?” My hypothesis was that attendance of an after school learning environment would help students gain greater levels of academic achievements and confidence. This would be due to the additional teacher support provided which would help explain the requirements of assessment tasks and impact the students’ confidence. Furthermore a positive learning environment, free from distraction and unlike that available at home, would allow students to more focused time on their assessment tasks which could also improve their academic achievement.

Review of Literature

When considering the effects of an after school study support environment on students’, particularly those who have English as a second language (ESL), it was important to identify research that described a similar scenario to the learning space being created for this action research investigation. It soon became apparent that after school programs appear in a range of guises. Often the driving force is also not always to exclusively increase academic achievement, but a more general youth development stance through a range of classic extracurricular activities. These can include youth organizations such as the Boys and Girls Clubs of America (Hirsh, 2011). Furthermore, the location does not always have to be the school. For instance, the role of local libraries in the United States of America was highlighted by R. J. Rua (Rua, 2008). However, the learning space was an after school study support environment for students to receive access to a positive learning environment and/or to offer general academic assistance in accessing the literature, which provides the greatest similarity within the review of literature to school based “homework clubs”.

Cosden, Morrison, Albanese and Macias (2001) analyzed the benefits and the required structures of effective homework clubs.The homework-intervention components that were viewed as integral to the success of the program were the provision of (a) time, (b) a structured setting for homework completion, and (c) instructional support for students. This data also suggested that after-school homework-assistance programs can serve a protective function for children who are at-risk for school failure, particularly those who do not have other structured after-school activities or for those whose parents do not speak English at home. In general, it was noted that the effectiveness of a homework club is mediated by the availability of homework assistance at home, the quality of the after-school homework program and the nature of the homework assigned.

In a later article Cosden, Morrison, Gutierrez and Brown (2004) noted that homework projects had a particularly positive impact on students who were ESL learners. This reflects the majority of students who would be involved with the learning space at my present school. However, certain risks relating to after-school homework programs were highlighted, and taken into consideration for this intervention:

- Taking parents out of the homework “loop” may reduce parental opportunities to communicate with their child about school

- Homework support cannot be coordinated by classroom teachers

- Required participation in homework activities may prevent participation in other activities that would benefit student bonding to peers and the school

Joseph Sancore (2002) employed the expression “children home alone” to describe a scenario of children often at home, unaccompanied for several hours a day who are at risk to the distractions of the outside world and utilizing their time in non-thoughtful activities. These non-thoughtful activities were identified asexcessive watching television, gaming, socializing on the telephone and other such activities which did not extend of complement school related goals. He describes homework clubs as an important alternative to this bleak scenario, wherein almost all students benefit – but especially those who struggle with traditional learning models. Yet it was also noted that for this to happen, professional development would be required to help teachers create stimulating homework assignments. In hisarticle, it was identified that such homework task must extend classroom learning, engage students with powerful read-aloud opportunities, guide learners to read and write interactively, provide opportunities for shadowing the students during the act of reading or writing, match individuals with appropriate resources, invite learners to make choices, encourage students to be reflective and motivate learners to evaluate their own progress. These requirements go well beyond my initial study, and the learning space itself, though it would be an interesting avenue for directed professional development in the future.

The creation of the learning space, does not, in itself, guarantee academic progression. Bender and Stahler (1996) studied homework centers run by the Pottstown Homework Centre Partnership, in Pottstown School District, Pennsylvania. This study compared academic development between 1st and 4th quarters of 34 randomly selected non-participation students from the school district with 34 low participation students (who averaged less than one attendance per week) and 34 high participation students (who averaged at least one participation per week). The results from this study clearly demonstrated that there was an increase in achievement of students who participated on a regular basis but there had been no impact on the low participation students or, unsurprisingly, the non-participants. This highlighted the importance of encouraging students to attend the learning space more than once a week.

In conclusion, the review of literature highlights the positive impacts of an after-school homework club, on which the learning space is modeled, especially those students with the greatest needs. However, it also highlights some of the issues related to moving this opportunity away from the family unit and the impact of poorly designed homework tasks. Crucially, and of greatest concern to my own intervention, is the impact of attendance which may be difficult to ensure with the voluntary attendance model developed for our learning space.

Method

Research Design

To answer my research question I used an action research intervention study with repeated measures across two group pre/post design. The independent variable was the presence and availability of the learning space for 3 months whilst completing of a grade 10 MYP Science unit on Car Safety. The dependent variables will pre/ post academic achievement and confidence. This would provide data for causal-comparative research.

Intervention

The intervention was the introduction of the learning space (see appendix A for proposal details) to the after-school schedule in January 2014. Due to the rotation of the two grade 10 classes it was possible to make a comparison of the impact of the intervention since the first group would complete my car safety unit before the introduction of the learning space and the second group, who are taught from January, would receive the additional learning space access.

Sample

The learning space was available to all students at Northbridge International School of Cambodia (NISC). The secondary school student demographics are as follows:

| Sample size | 134 |

| Age Range | Grade 7 to10 (12 to 16 years old approx.) |

| Sex Distribution | 40% Female 60% Male |

| Nationality Breakdown | Cambodia 52%, Korea 16%, Australia 4%, USA 4%, Thailand 2%, Pakistan 2%, Germany 1%, Malaysia 1%, Afghanistan 1%, Kenya 1%, France 1%, India 1% plus Singapore, Austria, Peru and China |

| Location | Northbridge Community, Phnom Penh, Cambodia |

| Other characteristics | NISC is a fee paying school on the suburbs of the city which has recently become an IB World School with now two cohorts completing the IB Diploma to date. |

However, this intervention will only consider the grade 10 that had completed the previous academic year at NISC and this sample demographics are as follows:

| Sample size | 27 |

| Age range | 15 to 19 years old |

| Sex distribution | 46% Female 54% Male |

| Nationality breakdown | 44% Cambodia, 18% Korea, 7% USA and Australia, 4% Pakistan, Kenya, China, Malaysia, India and Thailand |

| ESL students (paying for additional support) | 4 students |

| English language B students | 5 students |

| Notes | These students were only fully introduced to the MYP during grade 9. |

The two groups taken from this sample were known in school as 10A and 10B and hence these were groupings of convenience. However, these classes had been designed to have a similar academic level and with a similar distribution of ESL students. There is no academic streaming at our school.

Instrumentation and DataCollection

The pre-intervention academic achievement data was the final criterion levels total in MYP Science from the culmination of grade 9 records. In sciences, students have the opportunity to gain a maximum level of 6 for each of the six criterion. The final level for each criterion must then be added together to give a final criterion levels total for sciences for each student. Therefore, the maximum final criterion levels total for sciences will be 36 (International Baccalaureate, 2010).

The post-intervention (and control) academic achievement data was the final criterion levels total in MYP Science following the completion of the grade 10 car safety unit (See appendix B), where all six criterion were also assessed.

The confidence in Science survey (Appendix C) was used to develop a comparison with a students’ confidence of success in MYP Science before and after the intervention (and control). Scores from the confidence in science survey were allocated:

0 = strongly disagree

1 = disagree

2 = agree

3 = strongly agree

With 10 questions within the survey each student will receive a pre and post score out of 30.

Threats to Validity

Maturation – group 2 will complete the car safety unit 3 months later with additional MYP Science experience

History – All participants could have been impacted by different prior experiences although this should be reduced as there was only one grade 9 teacher of Science.

History – The unit related to the intervention is Physics and there may be historical reasons why certain students perform better in this science specialism. However, the criterion related assessment of the MYP is skill based on not subject specific so this should reduce the impact.

Mortality (loss of students) – There may always be students who relocate during the academic year.

Results

To answer my research questions I used ttest analysis to assess whether or not there were significant differences between the two groups with respect to achievement and confidence in MYP Science. To consider the effect on ESL students, the comparison between two sub-groups containing only ESL students is replicated.

Achievement

An unpaired t-test did not quite show a statistically significant improvement in achievement in for the experimental group (t=1.814, df=24, P value==0.0822). Table 1 shows related means and standard deviations.

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations of Group Gains

| Group | Control | Intervention |

| Mean | -5.1 | -1.3 |

| SD | 6.51 | 3.14 |

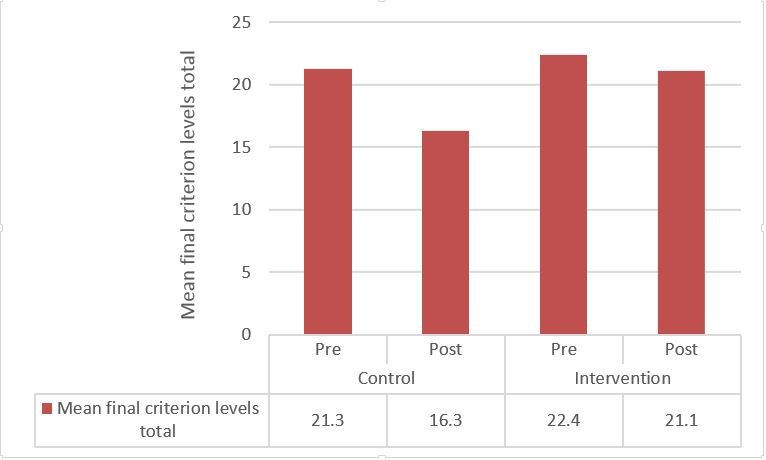

Figure 1 below demonstrated the mean pre and posttest scores in achievement for the control and experimental classes. Notice that the mean decreased for both groups but the intervention group’s performance decreased less.

Figure 1. Visual representation of mean pre/post tests for each group in achievement

Confidence

To understand whether the treatment affected students’ confidence in MYP Science the change between pre and post-tests was analyzed. The unpaired t test showed that although the confidence of the invention group increased and the control group decreased, overall this was not statistically significant (t=0.6990, df=35, P Value=0.4910). The related means and standard deviations are shown in Table 2

Table 2: Means and Standard Deviations of confidence in Science

| Group | Control | Experimental |

| Mean | -0.5 | 0.5 |

| SD | 4.26 | 2.43 |

Figure 2. Visual representation of pre/post scores in confidence in MYP Science

Attendance

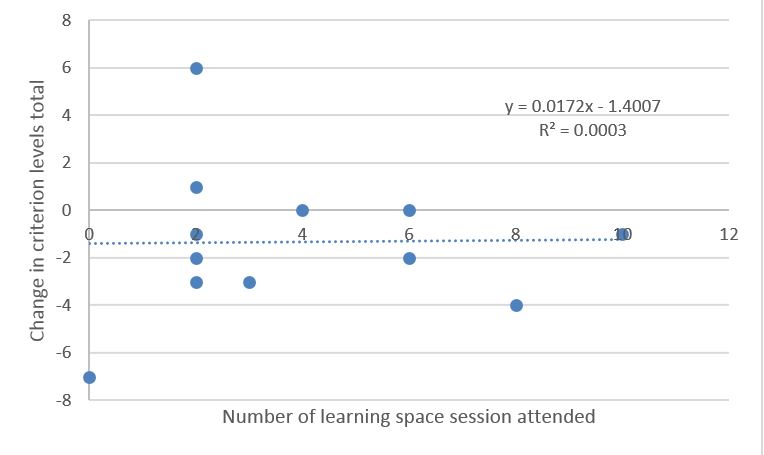

Within the literature research it was highlighted that attendance is an important factor on academic improvement related to after-school homework club attendance. As the number of times all students attended the learning space had been registered it was possible to analyze the intervention group data to see if the learning space study followed this trend.

Figure 3. Visual representation of the relationship between Learning Space attendance and change in academic achievement.

The near vertical trend line and a low R2 value indicate that in this study there was not a relationship between attendance and increased achievement. However, it should be noted that even the student who attended the most would have only met the criteria of a low attendance student, of attending less than once a week, as identified by Brender and Stahler (1996).

Achievement (ESL)

An unpaired t test does not show a statistically significant improvement in achievement for the experimental group (t=0.497, df=6, P value=0.6687). Table 3 shows related means and standard deviations of ESL students only.

Table 3: Means and Standard Deviations of group changes of ESL students only

| Group | Control | Intervention |

| Mean | -3.3 | -1.5 |

| SD | 7.54 | 1.91 |

Figure 4 below demonstrates the mean pre and posttest scores in achievement for the control and experimental classes. Notice that the mean decreased for both groups but the intervention group’s performance decreased by less.

Figure 4. Visual representation of mean pre/post tests for each group in achievement (ESL students only)

Confidence (ESL)

To understand whether the treatment affected students’ confidence in MYP Science the change between pre and post-tests was analyzed. The unpaired t test showed that the confidence of the ESL invention group increased and the ESL control group decreased. However, for this sample, this was considered statistically significant (t=3.0358, df=5, P Value=0.0289). The related means and standard deviations are shown in Table 4

Table 4: Means and Standard Deviations of confidence in Science

| Group | Control | Experimental |

| Mean | -2.0 | 0.5 |

| SD | 2.94 | 1.73 |

Figure 5. Visual representation of pre/post scores in confidence in MYP Science (ESL students only)

Attendance (ESL)

There is not a large enough sample range to fairly analyze the relationship between Learning Space attendance and change in criterion levels total for the ESL sample.

Discussion and Action Plan

The learning space intervention did not show a statistically significant improvement in academic achievement or confidence for all students in the study. However, for the ESL students it was shown to have a statistically significant impact on their confidence, which was originally hypothesized. However, the data also highlights that a lack of regular attendance of the Learning Space could also have been a major factor in this as highlighted by Brender and Stahler (1996). Over the intervention period the attendance was steadily growing and the full impact of the Learning Space may only be identified as it continues into the future.

In short, for the Learning Space to have further measureable impact, actions must be put into place to increase the number and regularity of students attending. This could be achieved with a combination of features designed to both attract students and occasionally coerce them. One of the key points discussed by the school faculty was the type of attendance expected of the Learning Space. It was decided that the Learning Space should not be a place that students are sent to for having not completed homework or as a form of punishment. However, this study also highlights that many of the students in greatest need are often not initially willing to take regular advantage of such an opportunity. Therefore, for those students at greatest risk it may be worth incorporating learning space attendance into student behavior contracts. In an attempt to attract students, a schedule of focused subjects and relevant additional supporting teachers will be developed – for instance Math Monday and Science Thursday. Teachers will also be encouraged to promote special sessions in the Learning Space that will focus on supporting a specific assessment task, rather than the teachers own room.

References

Bender, D. S., & Stahler, T. M. (1996, Novemebr). After School Homework Centres: A Succesful Partnership. Middle School Journal, 28(2), 24-28.

Cosden, M., Morrison, G., Albanese, A. L., & Macias, S. (2001). When Homework is not Home Work: After-School Programs for Homework Assistance. Educational Psychologist, 36(3), 211-221.

Cosden, M., Morrison, G., Gutierrez, L., & Brown, M. (2004). The Effects of Homework Programs and After-School Activities on School Success. Theory into Practice, 43, 220-226.

Hirsh, B. J. (2011, February). Learning and Development in After-School Programs. The Phi Delta Kappan, 92, 66-69.

International Baccalaureate. (2010). Middle Years Programme Sciences Guide. International Baccalaureate Organisation.

Rua, R. J. (2008, November). After-School Success Stories. American Libraries, 39, 46-48.

Sanacore, J. (2002, November – December). Homework Clubs for Young Adolescents Who Struggle with Learning. The Clearing House, 98-102.

The World Bank. (2014). World Bank – Data: Cambodia. Retrieved May 30, 2014, from The World Bank: http://data.worldbank.org/country/cambodia

Weiss, H., Little, P., Bouffard, S. M., Deschenes, S. N., & Malone, H. J. (2009, April). What Happens Outside School to Improve What happens Inside. The Phi Delta Kappan, 90, 592-596.

Appendix A – Learning Space Proposal

The school recognises that our students are often not adequately supported as learners beyond our walls due to a range of language and cultural issues. It is hoped that “The Learning Space” will combat this issue by providing a supportive environment conducive to learning.

The environment

Refined from a list produced a grade 9 homeroom group whilst discussing effective learning environment during an approaches to learning (AtL) session.

- Quiet space where people can use headphones if they want to listen to music

- A range of seating options – couches, large desks (where multiple people can work together and smaller desks where a single person can spread out there stuff)

- Snacks e.g. popcorn or fruit to provide extra energy

- Teacher chaperoned (teacher present and available for help)

- Peer support (older/ other students trained to help)

- Time from end of school until the last bus

- Grade level specific assignment calendars

Location

The multipurpose room (5101) has been offered and will be further developed to fit the varied requirements.

Staffing

Jordan and Neil will each initially support two sessions a week to help provide consistency through the initial launch period. Eventually this will be supported by all secondary staff sign-up rotation.

When supporting the learning space it is imperative that teachers rotate around and help get students started by reviewing the tasks.

Attendance

Attendance will be monitored with a sign in sheet but this will just be used to track overall impact and to help teachers identify those student using this support tool.

Students may be advised to attend the learning space by a teacher with associated guidance on what to do which can be should be shared with the learning space team

Launch

“The Learning Space” will open in the second week of the new semester in January 2014. This will be supported with posters/ a video/ student notices

Appendix B – MYP Science Car Safety unit planner

NIST MYP Unit Planner

Unit title |

Car Safety |

| Subject and grade level | 11 Science |

| Time frame and duration | 22 lessons |

Stage 1: Integrate significant concept, area of interaction and unit question

Area of interaction focusWhich area of interaction will be our focus? |

Significant concept(s)What are the big ideas? What do we want our students to retain for years into the future? |

| Health and social educationIn this unit students will:Consider ethical and safe use of transport

Reflect on their own behaviour to make informed choices

|

Sudden change can have dramatic impacts |

MYP unit question |

| Does speed kill? |

AssessmentWhat task(s) will allow students the opportunity to respond to the unit question? What will constitute acceptable evidence of understanding? How will students show what they have understood? Which MYP objectives and criteria will be addressed? |

||

| Criterion | Assessment Task | MYP Objectives assessed |

| AB | Car Safety Leaflet | Criterion A

Criterion B

|

| C | Car Safety End of Unit Test | Criterion C

|

| DEF | Collisions Investigation | Criterion D

Criterion E

Criterion F

|

Stage 2: Backward planning: from the assessment to the learning activities through inquiry

ContentWhat knowledge and/or skills (from the course overview) are going to be used to enable the student to respond to the unit question? What (if any) state, provincial, district, or local standards/skills are to be addressed? How can they be unpacked to develop the significant concept(s) for stage 1? |

|||

Knowledge and Understanding

|

Skills

|

||

| Approaches to learningHow will this unit contribute to the overall development of subject-specific and general approaches to learning skills?What approaches to learning skills will be explicitly taught during this unit? | |||

| ATL Skill | Feature | Explicitly taught in context of… | |

| Organisation | Using time effectively in class Meeting deadlinesCreating personal goal settingBeing organised for learning | Expected progression during investigationClearly identified and discussedUsing required knowledge checklist

Research scaffolding/ Revision checklists |

|

| Collaboration | Analysing others’ ideasUsing the ideas of others criticallyRespecting others points of view | Forces and Motion conceptual review task with individual, pair share search for misconceptions | |

| Communication | Being informed by a variety of media | Comparison of drink driving advert strategies | |

| Information Literacy | Referencing sources in a bibliographyIn-text referencing (citing) | Car Safety task support materialsCar Safety task support materials | |

| Thinking Skills | Generating ideas through brainstormingChallenging informationUsing the inquiry cycle

Logical progression of an argument |

Introduction to course promoting consideration of different contextsConsideration of car safety information sourcesUsing the scientific method

Embedded in the scientific method |

|

| Reflection | Reflecting at stages of the learning process | Course review requirements | |

| Transfer | Using knowledge and skills from other subjects | Media analysis discussed for drink driving advert consideration | |

Digital StandardsHow will this unit contribute to the overall development of the digital standards? |

|||

Data logging

Displaying data

Interpreting graphed data

|

|||

Learning experiencesHow will students know what is expected of them? Will they see examples, rubrics or templates? How will students acquire the knowledge and practise the skills required? How will they practise applying these? Do the students have enough prior knowledge? How will we know? |

Teaching strategiesHow will we use formative assessment to give students feedback during the unit? What different teaching methodologies will we employ? How are we differentiating teaching and learning for all? How have we made provision for those learning in a language other than their mother tongue? How have we considered those with special educational needs? |

||

Car Safety

|

|||

Speed

|

|||

Acceleration

|

|||

Kinematic Graphs

|

|||

ForcesReflect upon prior knowledge (in year 9 F=ma is introduced)

|

|||

Forces (Resultant)

Extension: Vector analysis including non-right angle forces |

|||

Forces (N3)

|

|||

Forces (Review)

|

|||

Ticker-tape

Further problems relating to ticker tape |

|||

| Car Safety EssayOpportunity for research, note taking, bibliography and in-text referencing formative assessment | |||

Breaking Distancesi) Equations of motion

ii) Friction

iii) Drink Driving

Plenary task evaluates understanding from all 3 bases. |

|||

| Terminal Velocity and unit revisionGroup task designed to encourage reflection of prior knowledge relating to resultant forces, distance-time graphs and velocity-time graphs of a parachute jump.Student choose revision tasks with advised

Unit knowledge check sheet is offered to support revision |

|||

Car Safety Test

|

|||

| Collisions investigation (4 x lessons)Practical investigation of collisions with differentiation available through guidance with task (highlighted with extension support relating to self-teaching of momentum and impulse) | |||

Car Safety test review and unit reflection

|

|||

ResourcesWhat resources are available to us? How will our classroom environment, local environment and/or the community be used to facilitate students’ experiences during the unit? |

|||

| Classroom specific:Key words, AOI, Significant concepts and guiding questions for display

Science Department: All required equipment

|

|||

Ongoing reflections and evaluation

In keeping an ongoing record, consider the following questions. There are further stimulus questions at the end of the “Planning for teaching and learning” section of MYP: From principles into practice.

|

|

Students and teachersWhat did we find compelling? Were our disciplinary knowledge/skills challenged in any way? What inquiries arose during the learning? What, if any, extension activities arose? How did we reflect—both on the unit and on our own learning? Which attributes of the learner profile were encouraged through this unit? What opportunities were there for student-initiated action? |

Include more challenging problems

Expressing of units in same style Emphasize vector component Check terminology consistency Equal and opposite reactions bring in

|

Possible connectionsHow successful was the collaboration with other teachers within my subject group and from other subject groups? What interdisciplinary understandings were or could be forged through collaboration with other subjects?

|

|

| AssessmentWere students able to demonstrate their learning?How did the assessment tasks allow students to demonstrate the learning objectives identified for this unit? How did I make sure students were invited to achieve at all levels of the criteria descriptors?

Are we prepared for the next stage? |

Yes |

| Data collection How did we decide on the data to collect? Was it useful? | To meet all objectives |

Appendix C – Confidence in Science survey

Confidence in science survey 1

Name: Grade:

| Statement | I strongly agree … | I slightly agree… | I slightly disagree… | I strongly disagree… | |

| 1 | I am confident about all of the terminology of science assessment task | ||||

| 2 | I am confident that I successfully complete a science assessment task | ||||

| 3 | I am confident about all the stages of a science assessment task | ||||

| 4 | I am confident that I can gain a level 6 looks on a science assessment task | ||||

| 5 | I am confident that I have the skills required for a science assessment task | ||||

| 6 | I am confident that I can cope with all the requirements of science assessment | ||||

| 7 | I am confident that I have the skills to achieve high levels in a science assessment task | ||||

| 8 | I am confident that there are no words in the science assessment task which I do not understand | ||||

| 9 | I am confident about my understanding of the science assessment instructions | ||||

| 10 | I am confident that I will be able to succeed with a science assessment task |

Leave a Reply